Is Australia a sitting duck for ransomware attacks? Yes, and the danger has been growing for 30 years

Australian organizations are an easy target for ransomware attacks, according to experts who yesterday issued a new warning that the government must do more to prevent agencies and businesses from falling prey to cybercrime. But the truth is, the danger has been increasing around the world for more than three decades.

Although a relatively new concept to the public, ransomware has its roots in the late 1980s and has evolved dramatically over the past decade, reaping billions of dollars in ill-gotten gains.

With names like Bad Rabbit, Chimera, and GoldenEye, the ransomware has established a mythical quality with an allure of mystery and fascination. Unless, of course, you are the target.

Victims have few options available to them; refusing to pay the ransom depends on having backup practices good enough to recover corrupted or stolen data.

According to a study carried out by the security company Coveware, 51% of companies surveyed were affected by some type of ransomware in 2020. More worryingly, typical ransom demands are increasing dramatically, from an average of US $ 6,000 in 2018 to US $ 84,000 in 2019, and a staggering US $ 178,000 in 2020.

A brief history of ransomware

The earliest known example of ransomware dates back to 1988-89. Joseph Popp, a biologist, distributed diskettes containing a survey (the “AIDS Information Introductory Disk”) to determine the risk of AIDS infection. Some 20,000 of these were reportedly distributed at a World Health Organization conference and via postal mailing lists. Unbeknownst to those who received the discs, it contained its own virus. the aids trojan falling asleep on systems before locking user files and charging “license fees” to restore access.

Joseph L. Popp, author of the Trojan Horse AIDS Information, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Although the malware was inelegant and easily undone, it gained media attention at the time as a new kind of cyber threat. The request for payment (by check to a PO Box in Panama) was primitive compared to modern approaches, which require funds to be transferred electronically, often in cryptocurrency.

It took over a decade before ransomware really started to proliferate. In the mid-2000s, stronger encryption enabled more effective ransom campaigns with the use of asymmetric cryptography (in which two keys are used: one to encrypt and a second, kept secret by criminals, to decrypt) , which even meant skilled skills. system administrators could no longer extract the malware keys.

In 2013, CryptoLocker malware reached global dominance, in part backed by the The GameOver Zeus botnet. Cryptolocker encrypted users’ files, sending the unlock key to a server controlled by criminals with a three-day delay before the key was destroyed. The network was shut down in 2014, thanks to a major global law enforcement effort called Operation Tovar. It is estimated to have had an impact on more than 250,000 victims and potentially 42,000 Bitcoin, valued at around US $ 2 billion at today’s appraisal.

Nikolai Grigorik, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

In 2016, several high-profile incidents involving the Petya ransomware prevented users from accessing their hard drives. This was one of the first significant examples of Ransomware as a Service, where criminal gangs “sell” their ransomware tools as a managed service.

Unknown criminal. Notify the authorities in case of discovery. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The following year saw arguably the most notorious ransomware attack of all time: the WannaCry attack. It struck hundreds of thousands of computers, including about 70,000 systems at UK National Health Service. WannaCry’s global impact has been estimated at US $ 4 billion.

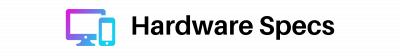

Screenshot of a WannaCry ransomware attack on Windows 8. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

More recent still was the Ryûk ransomware, which targeted local councils and national government agencies. But cybercriminals have also attacked specific private companies, including the largest refined petroleum distribution network in the United States, Colonial pipeline, the multinational meat processor JBS Foods, and Australia Canal Neuf network.

Is all ransomware the same?

There are hundreds of types of ransomware, but they fall into a few broad categories:

Cryptographic ransomware

In modern crypto ransomware attacks, the malware encrypts user files (“locking” the files to make them unreadable) and will typically involve a “key” to unlock files stored on a remote server controlled by cybercriminals. The first variants would require the victim to purchase software to unlock the files.

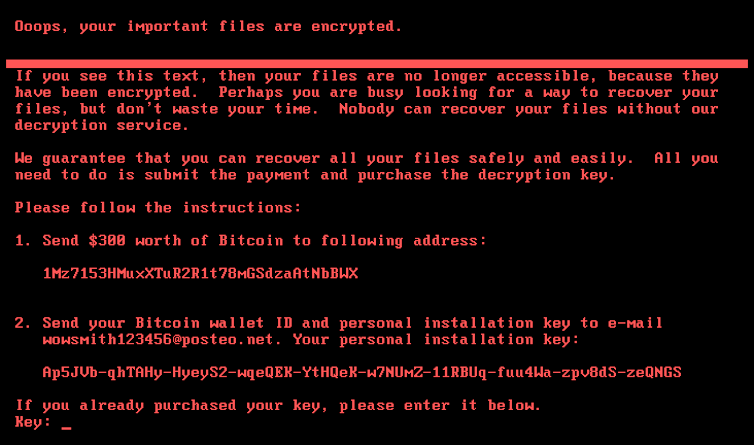

Ransomware Locker

Locker ransomware is typically a more complex type of malware that targets a user’s entire operating system (such as Windows, macOS, or Android), hampering their ability to use their device. Examples might include preventing the computer from starting, or forcing a ransom note window to appear in the foreground and preventing interaction with other applications.

Although the files are not encrypted, the system is generally unusable by most users (as you would likely need another system or software to extract the files). In some cases, ransom demands refer to government agencies with threats of investigations relating to tax evasion, possession of child pornography or terrorist activities.

Motormille2, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

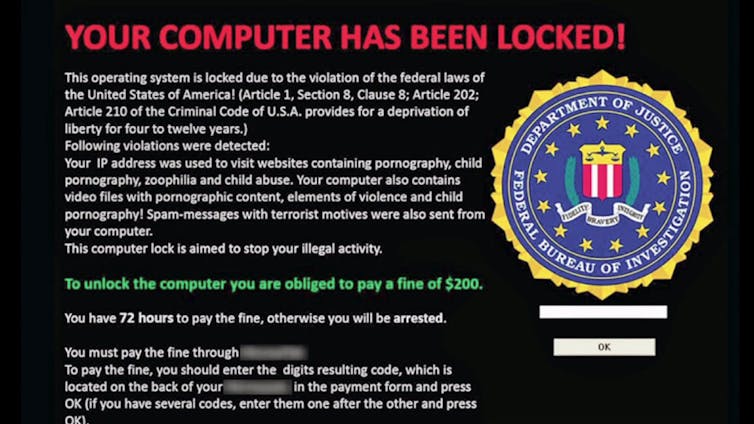

Leak

In a leak attack, the data is not encrypted but rather is stolen from the victim and held by cyber criminals. It is the threat of public disclosure alone that is used to secure payment of a ransom. From 2020 to 2021, reported occurrences of unencrypted ransoms have doubled.

Double extortion

Double extortion is an alarming development in which not only is payment required to secure the release of the organization’s encrypted data, but there is an additional threat of public release as well.

Author provided

This approach typically involves data being stolen from the organization during the malware infection process and then sent to servers managed by cyber criminals. To encourage payment, snippets can be posted on public websites to prove data ownership – coupled with threats to publish the remaining data.

Ransomware as a Service (RaaS)

The first ransomware was developed by individuals, but like all software, ransomware has come of age. It is now a multi-billion dollar industry (a estimated at 20 billion dollars in 2020) and is just as well designed and implemented as any commercial software.

Just as Microsoft’s Office 365 has become a service, where instead of buying the software you pay a monthly or yearly subscription, so does ransomware. Ransomware as a Service (RaaS) allows criminals to obtain services, usually in exchange for a ransom cut.

Read more: Hold the news as a ransom? What we know so far about the Channel 9 cyberattack

To pay or not to pay?

Most law enforcement agencies advise against paying ransoms (just as many governments will not negotiate with terrorists), as this is likely to encourage future attacks. But many organizations pay nonetheless. It is interesting to note that the public sector is passing the baton to ten times more money to disclose their records as victims in the private sector.

Paying a ransom is often seen as the lesser of two evils, especially for small organizations that would otherwise be completely shut down due to disruption to their systems. Or, if you’re lucky, the malware will already have a publicly available antidote.

But paying the ransom does not guarantee that you will get all of your data back. By a estimate, an average of 65% of data was typically recovered after the ransom was paid, and only 8% of organizations managed to restore all of it.

With criminal groups now reaping multi-million dollar profits, ransomware attacks are likely to target large organizations where the rewards are greatest, perhaps focusing on holders of valuable intellectual property such as the healthcare and medical research industries. The Internet of Things (IoT) will likely be a target of cybercriminals, with global networks of connected devices held hostage.

While large organizations are likely to have appropriate technical safeguards, educating users is always key – a single person’s lack of judgment can always bring an organization to its knees. For small businesses, finding (and following) cyber advice is crucial.

Given the enormous scale at which cybercriminals operate today, we have to hope that law enforcement and software security engineers can stay ahead of the game.

Read more: Holding the world hostage: The top 5 most dangerous criminal organizations online right now